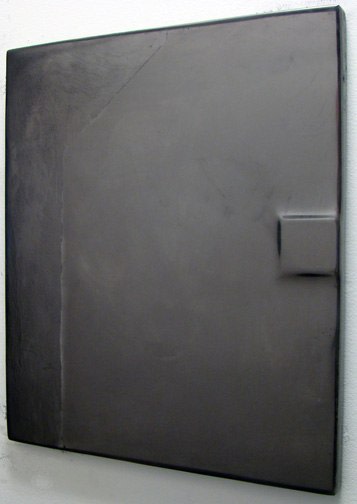

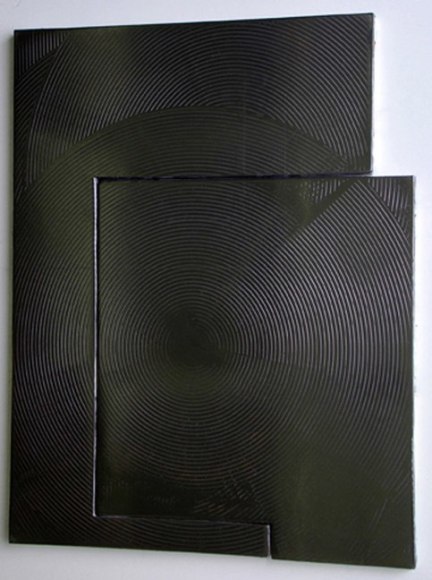

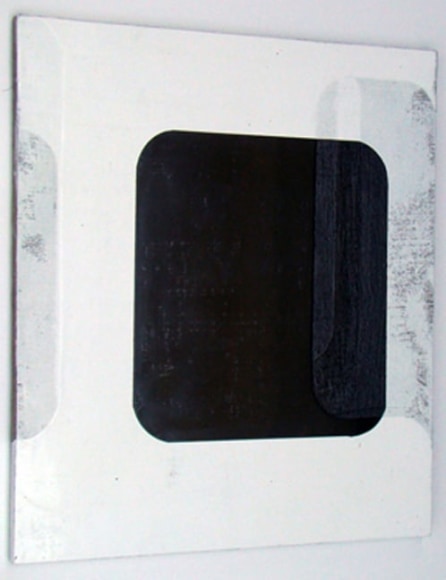

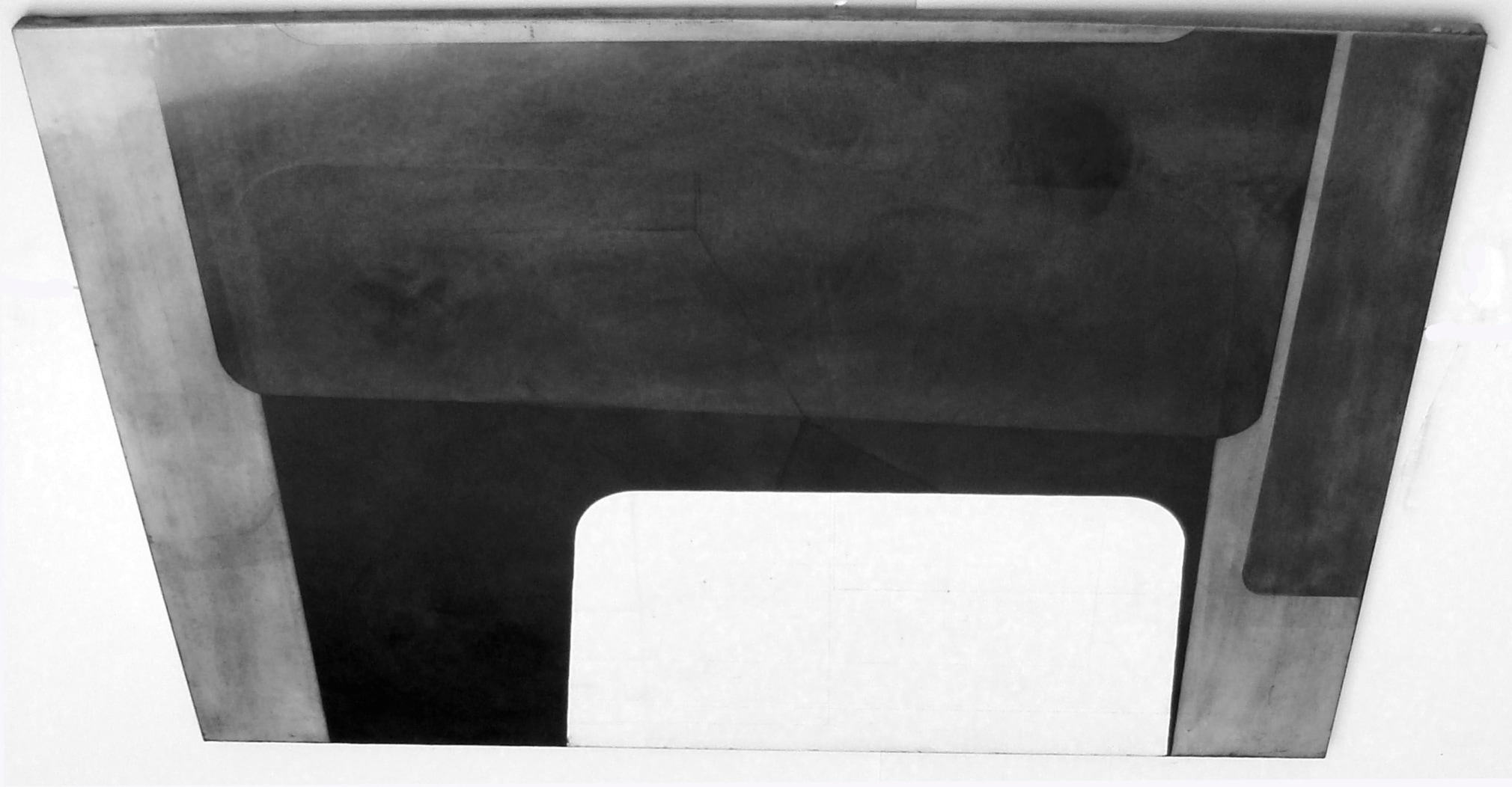

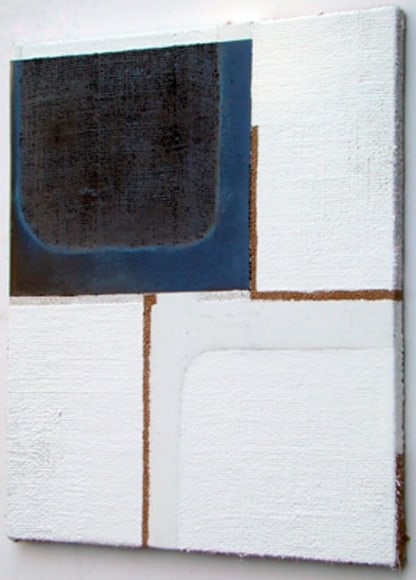

Stux Gallery is pleased to present a new body of work by James Busby, opening on September 16, 2010. In these paintings, Busby extends the innovative technique of his previous White series, which involved carefully building up the surface of the work with layers of gesso, which are then sanded down, polished, and given sculptural dimension. The abstraction of these works has often been linked to certain effects of Russian Constructivism or Suprematism. In the new White and Black series, he adds powdered graphite to the surface of the formed gesso, extending the abstract qualities of the earlier work in a deeper engagement with a new range of subtle surface effects and textures.

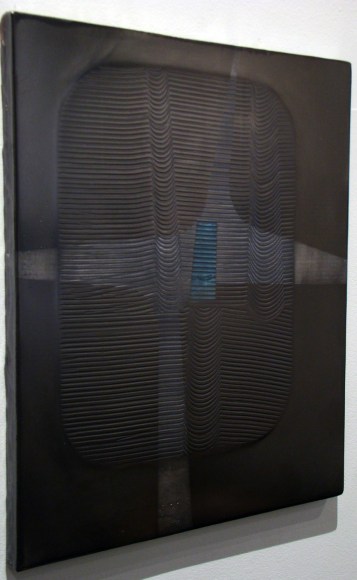

Already poised somewhere between painting and sculpture, the addition of graphite to the surface raises the spectre of drawing as well. These new works play with their substrates, which include materials such as shaped MDF and linen, by building up the gesso in relatively few layers, allowing the weave of the linen to peek through at the edges, for example. The darker tone provided by the rubbed graphite surfaces allows subtle variations in the surface texture of the works—which in any given work can range from shimmering, highly burnished to flat/matte—to become visible, even if just barely. Engaging the edges of perception in a way that is similar to Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings, these shaped works also engage an element of the generative structure of Frank Stella’s early work. Playing on the tension between the senses of vision and of touch, these tactile surfaces catch and reflect light in a way that shifts constantly, in response to the position of the viewer. In several works, application of the graphite to a black gesso base produces a surprisingly white reflective surface, one that reverses tone unexpectedly, snapping in and out of view like the delicate image on the bright surface of a daguerreotype.

The focus of these works is both process and mark-making. “I can’t just put a mark down without going back over it,” Busby says. In the process, what at first appear to be very improvisational, even casual gestures and residual brushstrokes are transformed into ciphers that refer to painterliness, rather than being it. The phantom of intentionality hovers over these works, and the longer one looks, the more difficult it is to determine which marks were accidental, and which might have been deliberate. This reframing of the element of chance is integral to the critical depth of these works, as they continuously enfold conceptual strength in perceptual indeterminacy.