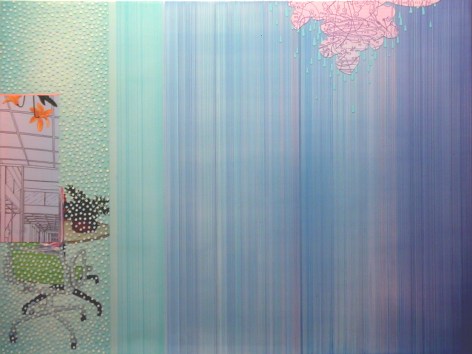

The pictures in Dion Johnson's paintings are so clear and distinct that dogs and cats could

understand them. That's one reason why critics who like their art to be obscure and difficult

(all the better to flaunt their brainy ability to translate it) have so little to say about works like

these, in which simple things are presented in such a straightforward manner that you'd have to be

doofus to miss the point. This tells us two things about Johnson's paintings:

1.) They have consequences. Looking at them is risky business because they remove the safety

net provided by the illusion of detached observation. They also eliminate the bet-hedging

relativism that accompanies standard ideas about art's identity as an incomplete entity in need of

interpretation - the more complicated and multi-layered the better. Johnson's profoundly

superficial works are not codes to be cracked nor signs to be deciphered nor texts to be analyzed.

Public utterances, they are concrete (and fairly sophisticated) instances of civilized sociability.

As such, they take decorum seriously. Refusing to separate matters of taste from larger questions

of manners, they do not concern themselves with private sentiments or unbecoming intimacies.

Instead, they invite one-on-one interactions, inciting viewers to behave in a variety of ways.

Whether you love them or hate them you have some kind of reaction; even middle-of-the-road

responses stand apart from the distant, uncommitted analyses often elicited by works of

contemporary art - and monotonously delivered by commentators of a conceptual (i.e.,

contemplative) bent. In every case, Johnson's unguarded yet well-heeled paintings hit us where

we live. Throwing their lot in with all types of social events, from casual encounters to highly

formalized exchanges (and everything in between), they traverse the fully visible world. Rather

than conveying neat morsels of meaning, Johnson's works lay all of their elements out on

beautifully crafted surfaces so that everything is visible all at once. Their immediately

recognizable images and vivid painterly incidents don't force viewers to dig out secret tidbits of

significance (in the manner of painstaking archaeologists). Nor do they presume that looking at

art has anything to do with uncovering emotionally loaded symbols (in the manner of tenacious

psychoanalysts). Likewise, they eschew the idea that art gets us to re-live momentous, lifedefining

traumas (as if art-viewing were some sort of therapy and viewers were patients in need

of healing). On the contrary, Johnson's levelheaded works simply set your eyes in motion.

Gliding across variously applied swoops, swishes, and smears of paint, your optical organs gain

speed, momentum, and energy as you rediscover what it's like to see the ordinary stuff of

everyday life anew - with the fresh-eyed enthusiasm of the first time.

2.) Specialists and professionals are in no better position to respond to Johnson's user-friendly

works than is anyone else. (In fact, approaching these simple but far from simplistic pictures

encumbered with the idea that meaning is an inert, passively transmitted entity puts one at a

distinct disadvantage.) Being curious about one's surroundings and the relationships that take

shape among their myriad components is all that Johnson's acrylics on canvas and plexiglass

demand. In the end, this turns out to be quite a lot. The shamelessly playful appearance of these

unpretentious paintings doesn't prevent them from making deeply serious, quasi-philosophical

propositions. Before them, it becomes clear that meaning does not originate from above

(in some transcendent realm of Timeless Ideals) and then trickle-down to earth-bound viewers.

Instead, it springs up from below, percolating through life's imperfections to brew more timely

truths. Most important, Johnson's paintings make this proposition by showing rather than telling:

They change a viewer's relationship to highfalutin ideas by locating such ordinarily ungraspable

abstractions in the present, however unglamorous and incomplete it may be. Never appealing to

the authority of historical precedents or to the ideas out of which they grew, these humble works

appeal only to the responses they generate. In them, everyday scenarios, recognizable objects, and

easy-assembly diagrams appear alongside a pretty thorough cataloging of the various ways paint

can be applied to a flat surface: brushed, combed, squirted, and squeegeed - even sculpted, cut,

and collaged. Viewers are thus compelled to participate in the unscripted stories that unfold

before them. Bringing grand aspirations and wild ambitions down to earth by emphasizing just

how extraordinary ordinary things can be, Johnson's refreshingly accessible pictures put the Pop

back into populist. Imagine an old TV on the fritz and you'll have an idea of the out-of-sync

scrolling flow that occurs when you look at these works. Then imagine that your set is picking up

about a dozen channels simultaneously - that, as the out-of-frame images jitter and roll across the

screen, they also flip from one program to another. This will give you an idea of how clunky and

plodding ordinary channel surfing is when compared to what takes place before Johnson's

animated paintings. Here, worlds do not collide as much as they momentarily frame one another,

gracefully segueing from one to the next. As your glance drifts across the smartly edited surfaces

of these pictures, elements that are the stars of some scenes become the supporting casts in others.

Things shift position with impressive equanimity. Plastic ants, coloring-book kids, and the daring

men of the flying trapeze have plenty of room to maneuver - and leave plenty of room for

viewers. The sweet appeal of Johnson's candy-colored palette and PG subject matter goes handin-

hand with the desire to draw viewers into open-ended dramas that begin with benign banalities

but whose outcomes are neither. Behaving as if nothing were more scintillating than the little

fugitive pleasures we sometimes steal from the jam-packed schedules that make up our lives of

constant, multi-tasking busyness, these paintings make room for aimless play. Surreptitiously

sneaking into the gaps between tasks and duties, commitments and obligations, they redeem lost

moments by giving form to time spent doing nothing in particular, when unformed notions drift

in and out of focus, sometimes giving birth to full-blown thoughts and at other times providing

more mysterious satisfactions. Johnson's endearing images bring innocence back into the picture

not by traveling back in time but by making space, in the present, for daydreams whose pleasures

are as intangible as they are undeniable.

-- David Pagel