Stux Gallery is pleased to present Chinese Relativity, a selection of Contemporary Chinese

painting and photography. Focusing, primarily, on the identity of the individual in relation to

the socio-political situation from which it occurred, this exhibition is to serve as a cross

section, rather than an absolute statement, of Contemporary Chinese painting and

photography today. Stemming, in part, from increasing cultural globalization, large

exhibitions such as the Taipei, Gwangju and Shanghai biennials have introduced

Contemporary Chinese art and artists to the global stage. This increased interest can be

traced, overtime, alongside political upheaval starting with the death of Mao Tse-tung in

1978 and the end of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

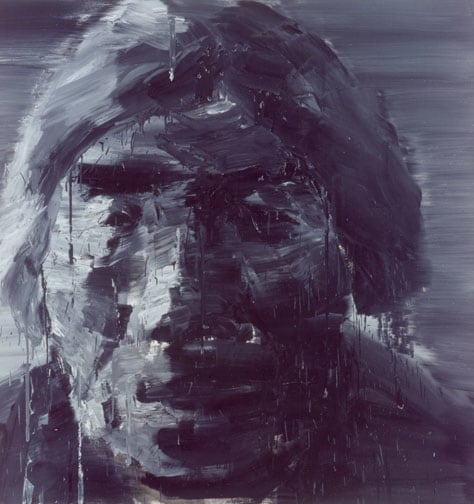

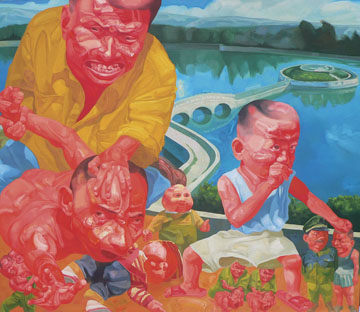

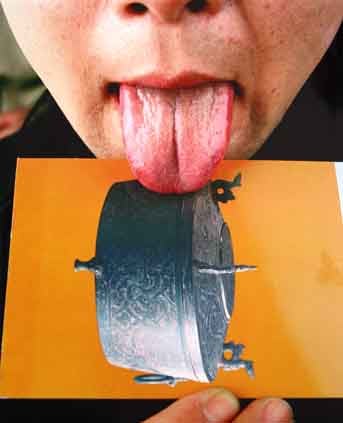

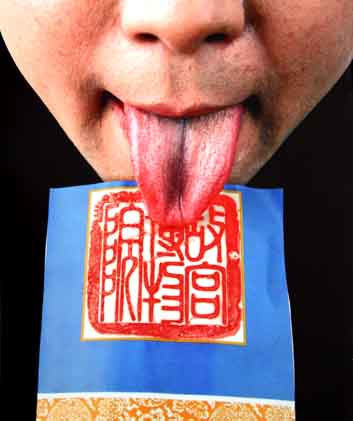

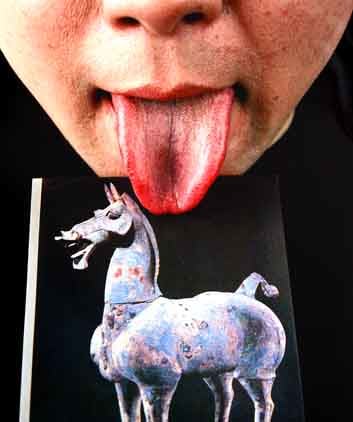

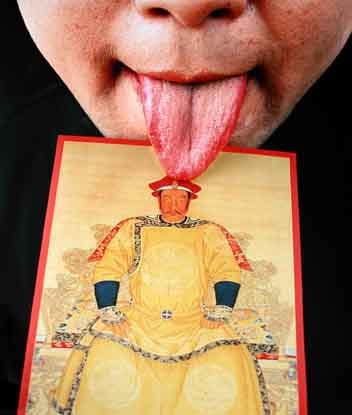

The 1990’s saw China’s shift toward an open market economy and the emergence of Political

Pop as a popular trend among painters in China. This began with the general appropriation

of Western Pop with American icons replaced with elements from earlier Chinese

propaganda posters (commonly seen during the Cultural Revolution). With time, these icons

were replaced with symbols from everyday life (Hong Hao, Yan Lei, Yan Pei Ming) and

Chinese history and tended to feature cheerful colors and an irreverent attitude. This Pop

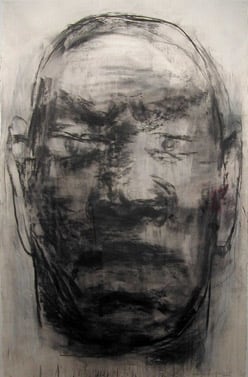

style was followed by, among others, Neo-Reality and Neo-Figuration (Yang Shaobin),

where emphasis was placed on everyday life, new political boldness and explicit personal and

social awareness.

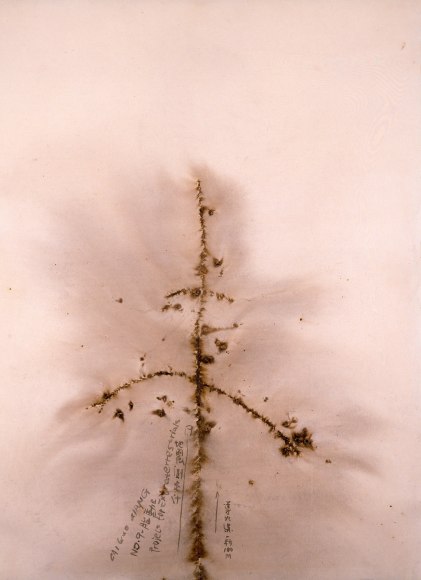

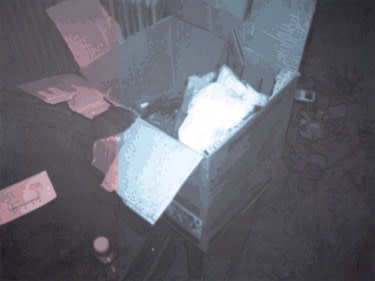

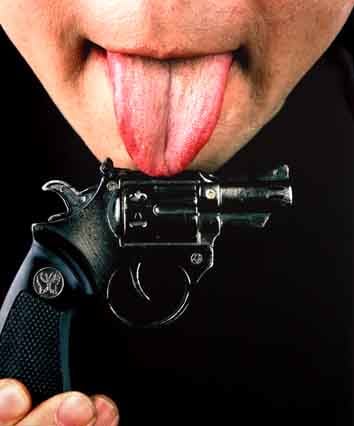

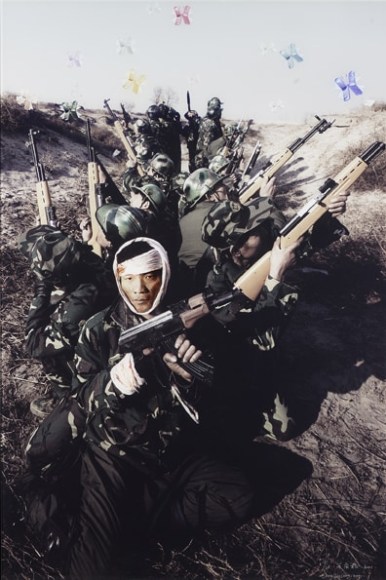

Spurred further by the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, artists began to search out

alternative environments in which to make their art under a less stifling regime (Cai Guo-

Qiang, Wei Dong). With an increase in migration of artists from Mainland China to the West

and back, opportunity arose for a great crossover and exchange of ideas. It is during this

period that we see the growth of experimental media originally banned in China, such as

performance and installation art, and a surge in the use of photography (Zhang Dali, Wang

Qingsong, Cang Xin) to document a more open and radical form of contemporary Chinese

art.

Severe political turmoil is bound to have a powerful relative effect on not only practicing

artists, but on the uncharted urban landscape that they inhabit. This landscape included the

mid-twentieth century art schools and academies of the People’s Republic of China, heavily

ensconced in technical schooling and laden with a hefty dose of realism. Such schooling

geared artists of the time to focus on Soviet socialist realism -- “art for the people” -- in an

attempt to build support for the presiding political forces. The imprint left by this academic

system on the artists of the 1980’s and 1990’s would be a significant one felt in the works of

Chinese artists for many years to come