In her painting Two Men Fighting Over a Thing That Makes Them Happy (2004)

Thordis Adalsteinsdottir introduces several new features into the subject matter of her

painting. First is the reference to Classicism or classical figuration, dating back to

Greek or Egyptian times. She prunes to the bare essence of two men in the midst of

battle, a common classical theme. Each of Adalsteinsdottir’s figures has archaic features,

but the body proportions are flattened and attenuated and yet the figure on the bottom,

rather than in an eyelock with his opponent, looks out at us with an expression that

seems to ask, “can you believe this is happening?” A poor little animal’s extremities are

being pulled in two directions, and this creature, the subject of the fight, seems to be the

real victim—the Helen of Troy in this battle scene. We as viewers can conclude that in

such fights there are no winners, only losers.

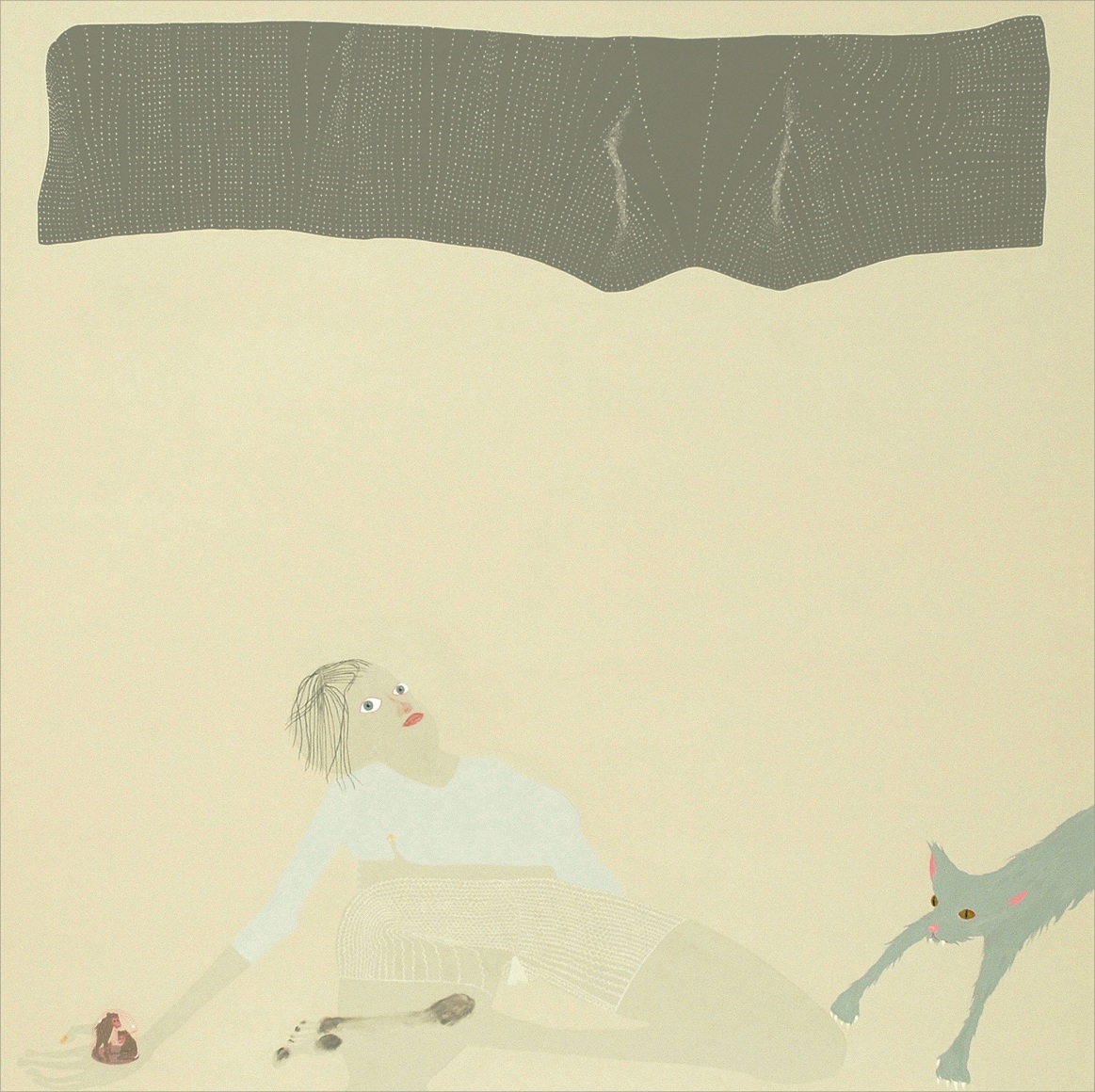

As a Psychoanalyst, it has been my experience that when a patient who has been severely

traumatized in life comes into my office, I am struck by a feeling that the story being told

to me has a quality of unreality like a fairy tale gone completely haywire and becoming a

nightmare. The more overt this experience of unreality is, the more I comprehend the

severity of the trauma that the person with me has experienced. When I stand in a room

with the paintings of Thordis Adalsteinsdottir, the sensation is similar. Her paintings are

the very essence of interior psychological space. The psychoanalyst R. D. Laing once

commented that when he looked at the paintings of Francis Bacon, he knew that Bacon

understood what it was like to be schizophrenic-- not being able to distinguish inside and

out. Clearly, Adalsteinsdottir understands Bacon as well, and she especially understands

how using monochromatic off-tones to fill the picture space lends intensity to

psychological tension. She also feeds that tension with bizarrely expressive and

sometimes atrophied figures that have become her signature. They often seem vulnerable

and youthful and one step removed from some unmentionable trauma.

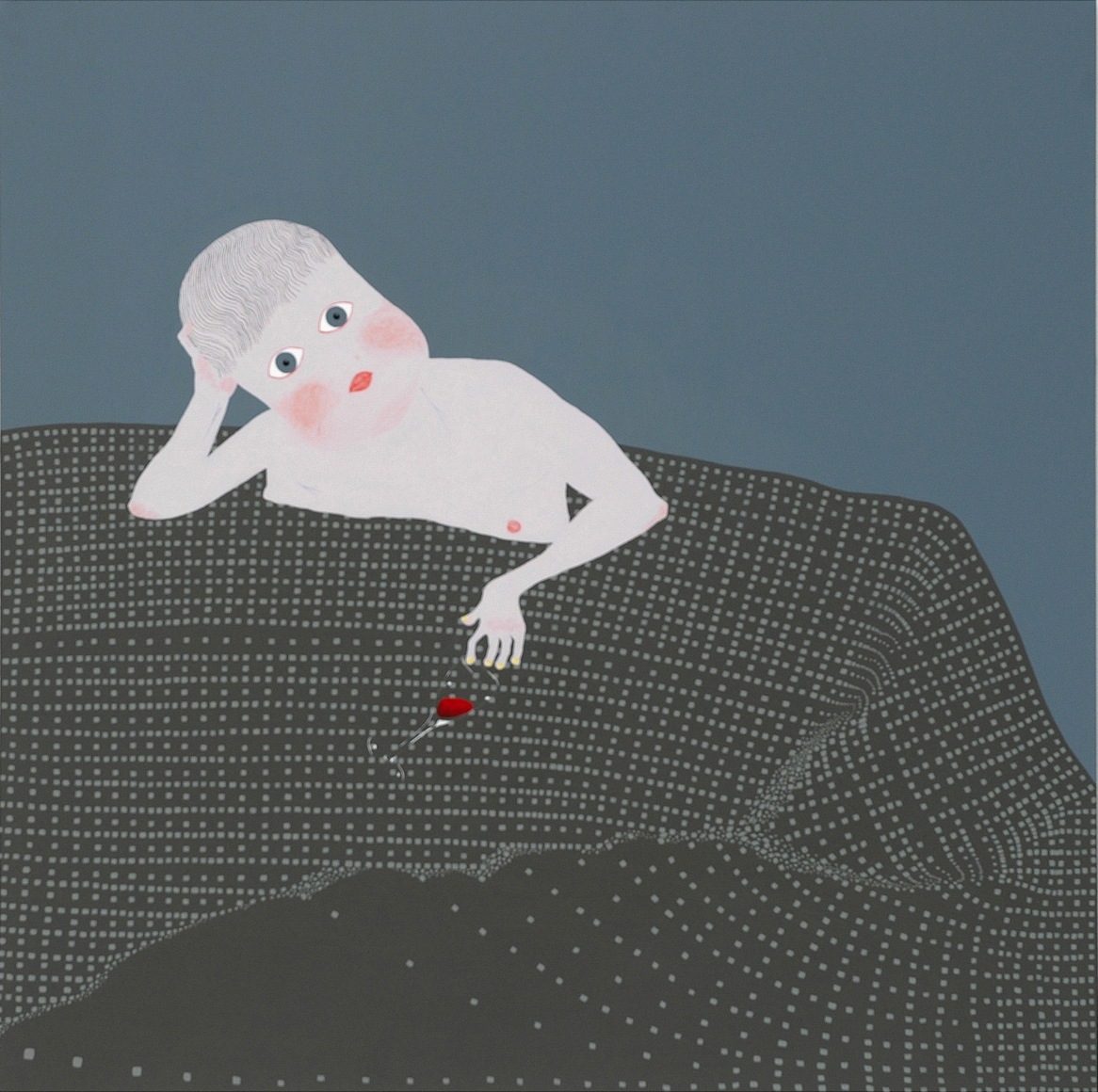

Owen in the Bathtub (2004) at first appears to be an innocent interior scene—a figure in a

bathtub. The reddened knees and the razor sitting on the tub ledge push Adalsteinsdottir’s

image beyond anything Bonnard ever could have dreamed up. The opaque water makes

the boy seem disembodied, and the idiosyncratic tiling design around the edges adds to

the effect that something is askew. The hieratic profile with one almond-shaped eye

equates the figure with ancient art and suggests the timeless universal struggle of

mankind. If water symbolizes our emotional state of being, then the murky water pushes

the metaphor. Yet, in our contemporary world we may think more of this vulnerable

creature on the brink of shame, exhaustion, and perhaps self-destruction.

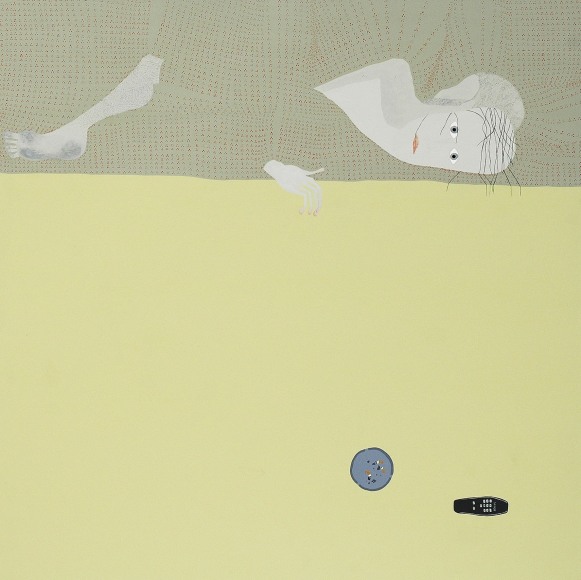

Adalsteinsdottir’s paintings seem to often call some aspect of the self into question. In the

diptych Woman and Bird with Ovaries (2004) she has created a narrative in which we are

not sure whether she is giving us the antithesis of an Annunciation or a reverant prayer.

A partially nude woman, red panties pulled below the hips, waves haplessly at an equally

hapless bird that is flying with ovaries in its claws. Is the bird arriving as bearer of a gift

or departing? Often birds are a symbol for the soul and for transformation, but now

Adalsteinsdottir seems to press the symbol, perhaps relegating the winged creature to a

thief. The vertical line that splits the image passes through the woman’s body, and no

matter which reading the viewer may bring to the painting, the diptych is a compelling

and painful reminder of the tenuousness of life.

-Douglas F. Maxwell