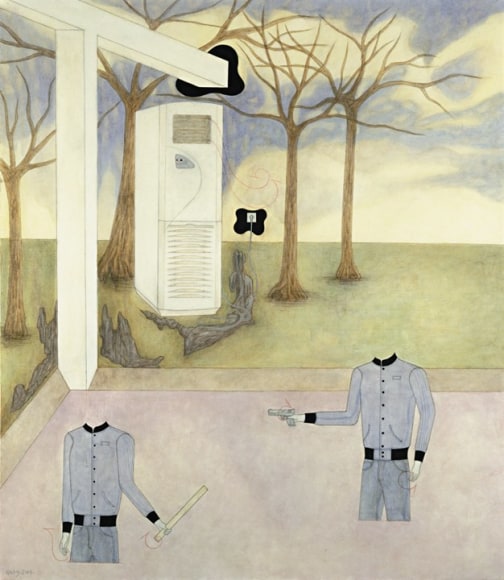

Part 2, which showcases a selection of well established figures of the Contemporary

Chinese Art scene, focuses primarily on the individual in relation to group socio-politics.

The show addresses several influences upon the selected artists, including: geographic

location, surrounding cultural influences, the movement from academia to popular

culture, reverence for history, the disavowal of iconography and the manner in which

material can convey political intent.

The world’s increasing interest in the Contemporary Chinese art scene has always been

understood in conjunction with notable episodes of political upheaval; starting with the

death of Mao Tse-tung in 1978 and including the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

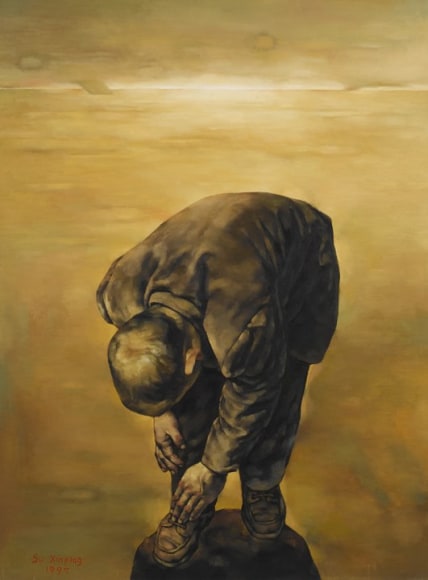

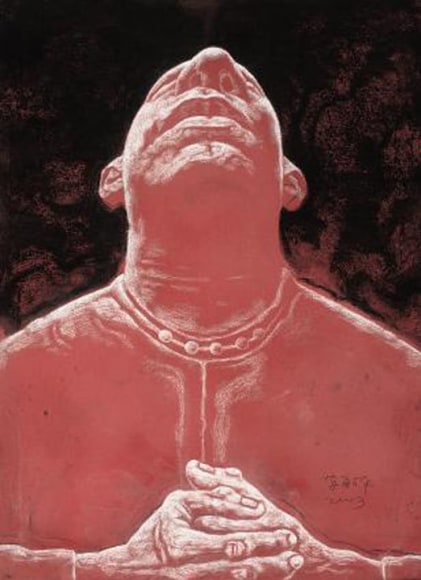

Developing their practices at this time, in art academies with a strong focus upon technical

disciplines, the imprint of academic social-realism is visible in the work of both Chinese

artists who later remained in their native country and in the work of those who spurned

the repression of Mao’s cultural revolution through geographic relocation. Regardless of

their working environment, the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 further exacerbated

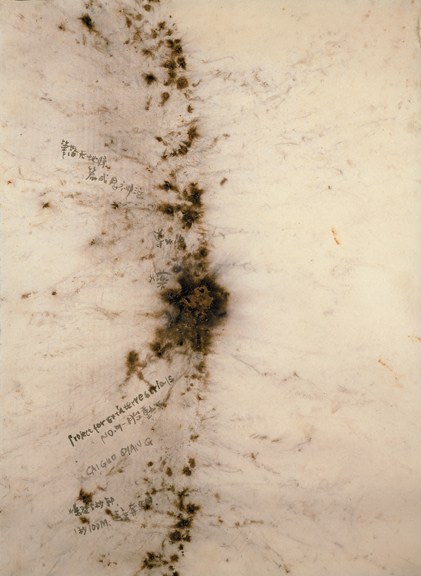

the Chinese art community to seek out alternative spaces – mental and physical – in

which to produce their work, thus leading to a greater exchange of ideas between

Mainland China and the West as shown in the works of Cai Guo-Qiang, Wei Dong and

Zhang Xiaogang.

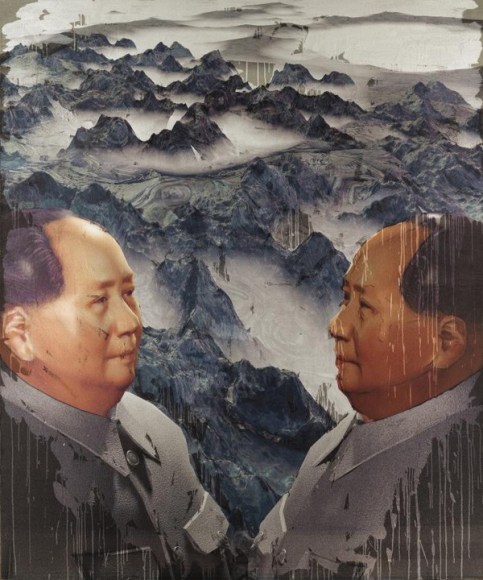

The 1990’s saw China shift toward an open market economy and the emergence of

Political Pop as a popular trend among painters in China. Here Western Pop and

American cultural iconography mingled with earlier forms of Chinese visual propaganda

creating potent juxapositions. The irreverence these artists displayed in ironically cheerful

palates soon allowed for the inclusion of symbols from everyday life, (Feng Mengbo, Su

Xinping, Fang Lijun) Neo-Reality and Neo-Figuration (Yang Shaobin, Zhang Fazhi,

He Sen), and a broadening of iconoclasm towards Chinese history. Also during this

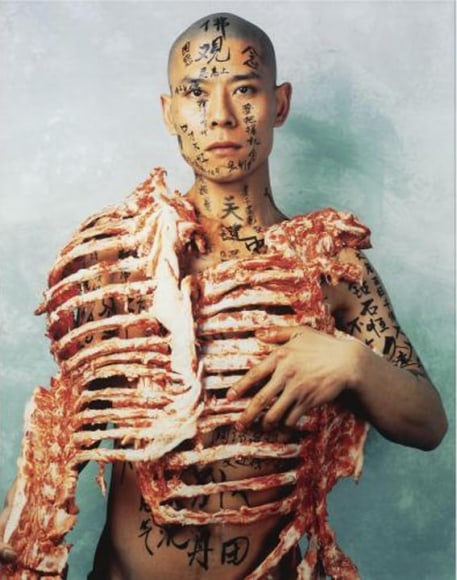

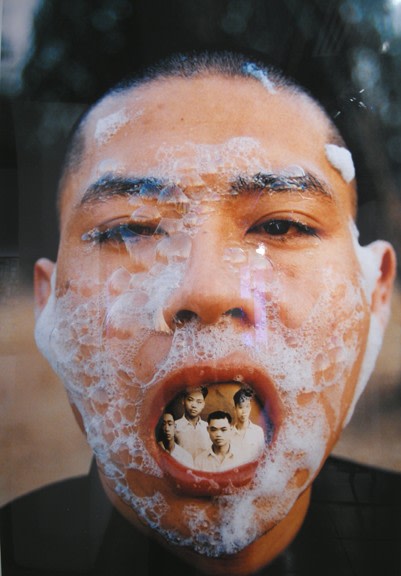

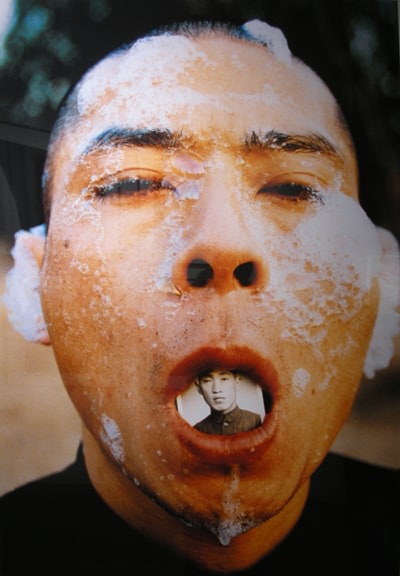

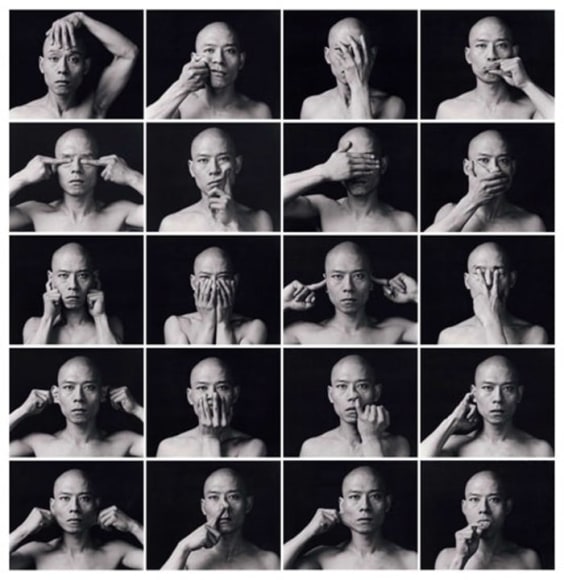

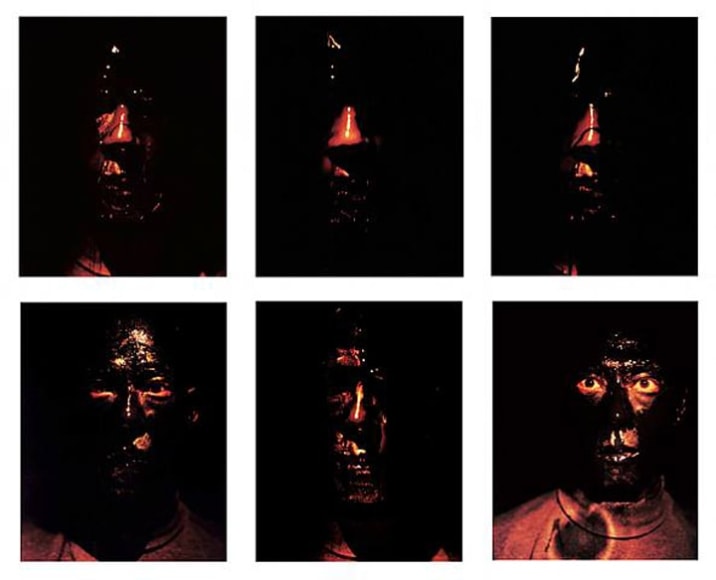

period, the use of experimental media, such as performance and installation art, originally

banned in China, grew in popularity. Similarly there was a notable surge in the use of

photography (Zhang Huan, Wang Qingsong, Wang Yaqiang). Thus, this group of

artists were able to declare a new political boldness and an explicit personal and social

awareness.

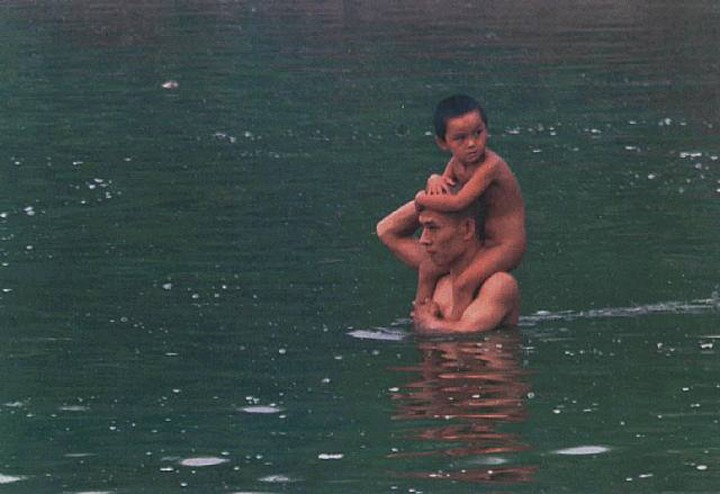

Severe political turmoil has always had a powerful relative effect on the practices of

artists. The above group is notable for their openness and inclusiveness in locating places

to work, methodologies to experiment with, imagery to dissolve and repurpose due to the

profoundly narrow surroundings their careers began in. The motto of Soviet socialist

realism – “Art for the people ” – has been modified by this selection of artists, to art that

locates the individual person within the group, whatever space they might inhabit.